I grew up in the Highlands of Scotland. This is a thing I say, when people (frequently) ask my origin. A script of sorts. It goes like this:

“Where are you from?”

“Scotland.”

“Where in Scotland?”

“The Highlands—just north of Inverness”

Normally, this is enough to satisfy the questioner at hand, but occasionally there is a part two:

“Where?”

“The Black Isle. Avoch.”

“Where’s that?”

“Just north of Inverness.”

This second part frustrates me the most. Why do people ask it? Nobody has ever heard of the fishing village of Avoch (pronounced aw-chk, due to the time-honoured farcical marriage of postcolonial misunderstandings and the slipperiness of the native Gaelic language). Nor should I expect them to, with its 900 residents, corner shop and solitary pub. Once a modestly successful fishing port, it has never reimagined itself as any kind of destination for any other major industry. It just kind of is.

Growing up within community

We moved to Avoch when I was three, and for all of my childhood years there, I was completely oblivious to the fact that we were ‘remote.’ We had a large house and garden, and from a relatively young age I was given the freedom to roam around for hours, playing in the ‘burn’ (a small river) or venturing out into the woods or down to the beach.

Beyond the borders of our small town, we were ensconced in a larger creative community across the Highlands. My parents, both avid patrons of the arts, were involved in all kinds of things throughout our childhood—contemporary dance groups, music festivals, theatre productions, visual arts exhibitions. Their friends and acquaintances from this formed a wide network of people and within that expansive context we found ample spaces to create, explore and imagine. We were privileged in so many ways—I don’t pretend that this was the experience of every child living in a small Highland town—but it was an almost embarrassingly idyllic upbringing that in no way felt lacking.

It wasn’t until I reached my teenage years that I started to understand this constraint of ‘remote.’ Remote, I learned, was why the band I listened to on my bedroom radio would be playing in the city four hours away, and not in nearby Inverness. Remote was the reason the delivery company added a surcharge to anything we ordered online. Remote was the fact that young people had to choose between staying in the area and doing service or labour work, or moving south to be able to study.

‘Remote from what?’

“Far, distant; removed, set apart,” is how the Oxford English Dictionary defines the word remote. From my vantage point of having chosen to make my life in many places frequently classified as such—the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, and now, Iceland, I am inclined to agree with my old schoolmate Magnus Davidson when he tweeted, “Remote from what? … London is remote from us.” Remote is presented to us incorrectly as if it were a quantifiable description of location. But what distance is remote? What direction does it go in?

Instead of giving us concrete answers to those questions, or indeed, informing us of why these distinctions are useful at all, governments and organisations and the powers that be have co-opted this helpfully indefinable word in order to make certain segregations in terms of provision of services and expectations of experience. This can extend to everything from access to childcare, poor phone or internet provision, limited transport infrastructure, to the distance to the nearest school or hospital.

The changing face of deprivation

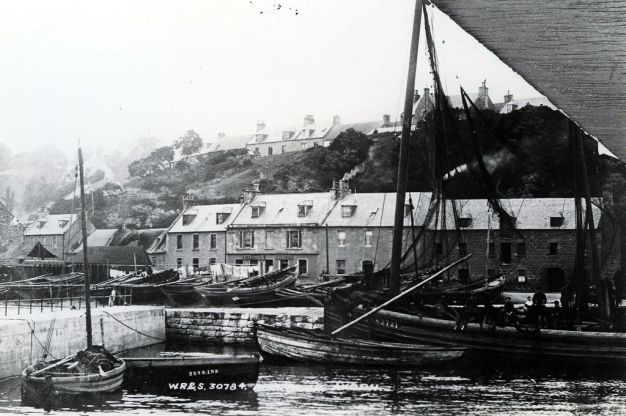

While it might seem reasonable on the surface that a small community might not have their own school or doctor’s practice, so often this reality is only a recent invention. Using my own hometown as an example, Avoch’s architecture is littered with ghosts that tell a very different story about its history than these authority voices would have you believe. The harbour, once the town’s focal point, was built in 1815 to a Thomas Telford design, before being extended in the early 1900s due to the sheer productivity of the fishing industry, which employed hundreds of people. Station Road, which I grew up on, is named for the fact Avoch once had a railway line running through it until the 1960s (with thanks to Mr Beechings). Within living memory, the highstreet boasted 13 different shops, almost all of which are gone, along with the doctor’s surgery, the council offices, the second school, the three churches and the bank. This is not a failing backwater hamlet, but a once thriving community that has been divorced from its ability to properly nurture and care for its inhabitants through the forced removal of amenities and services.

I don’t mean to have a rosy-eyed view of the past. The level of child poverty and ill-health in Avoch was well documented, especially after the herring industry collapsed in the early 20th century. But lifting the railway tracks, closing the doctors and expecting residents to travel to neighbouring towns and cities to do their banking or shopping only exacerbates inequality. Poverty might not look like bare-footed children with empty bellies these days, but it is still there, and more prevalent than you might like to think. As a child I saw the number of those who stood in line for lunch with their free school meals tickets. I knew kids who slept on the floor because their families could not afford a mattress.

Decline is a choice, not a fate

The language of remoteness suggests a kind of inevitability, as though communities like Avoch were always meant to be peripheral, always destined to be shrinking and playing catch-up to some imagined center. But remoteness, in this context, is not an accident of geography. It is a consequence of decisions, of policies that quietly siphon resources away, of transport links that were removed rather than maintained, of economic strategies that push young people to leave rather than invest in the possibility of staying.

To call a place remote is to place the burden on the place itself, rather than on the structures that have made it so. But remoteness is not just a matter of distance. It is a matter of attention, of will. Places like Avoch, like the Highlands, like so many communities dismissed as ‘far away,’ are not lacking in vitality, ambition, or imagination. What they lack—what has been taken from them—is the infrastructure to sustain those things.

This experience is only more acute in the age of the internet and global connectivity. When one can send an email off to almost every corner of the world with instantaneous responsiveness, why then do we still cling to these outdated notions of remoteness? This lack of consistency between considering another country as accessible and communicable, and parts of your own as wild hinterlands is completely baffling. At the least, it does away with the perceived understanding that remoteness is something to do with distance.

Broadband as the future?

The internet, when it works, offers a counterpoint to physical distance. It allows a young artist in Skye to collaborate with a musician in Reykjavík, or a small business in Shetland to sell to customers around the world, and communities in general to connect, organise and advocate in new ways. But even here, the gaps persist. The irony is, that in a world supposedly more connected than ever, these places remain treated as afterthoughts. High-speed broadband is promised but rarely prioritized. Phone signal is patchy. Digital infrastructure—so often touted as the great equaliser—is deployed unevenly, reinforcing the same hierarchies that physical infrastructure once did. Connectivity is treated as a privilege rather than a right and rural communities are left with unreliable broadband, prohibitive costs, and once again, an expectation that they should simply accept this as part of life on the margins. In theory, the internet should make geography less of a barrier. In practice, poor connectivity becomes yet another reason why businesses hesitate to invest, why remote work remains an option only for those with the right postcode, and why rural schools struggle to access the same resources as their urban counterparts.

The illusion of support; subsidies, but no school

It should be pointed out that these days there is undeniably a lot of money made available for ‘remote’ communities. This, in many ways, is both a gift and a distraction. There are funds for arts projects, for community initiatives, for schemes that inject bursts of activity into places that are otherwise left to make do. As a child, I benefited from these projects, and now, as an adult, I help run them. I know how much they matter. But they also serve to obscure the deeper issue: why do these communities have to rely on piecemeal, competitive grants in the first place? A drama club is wonderful, but what if the bus only comes twice a day? What if the roads are crumbling, the GP surgery closed, the local shop priced out of existence? These projects bring vibrancy, but they cannot replace the missing scaffolding of daily life. The grants keep coming, the applications are written, the short-term solutions appear—but the core issues, the lack of sustained, structural investment—remain shielded from view.

I eventually became one of the ones who left Avoch. I moved to Glasgow to study, and for a decade thoroughly enjoyed all of the wonderful opportunities well-connected city life has to offer. I have moved to various places since, and now find myself based in another version of ‘remote’: Reykjavík, Iceland. Here I find myself encountering a strange déjà vu. In Scotland, remoteness was a word reserved for rural areas, for fishing villages, island hamlets and scattered crofts. But here, even Reykjavík—by far the country’s largest city—is often spoken of in those terms. A capital city described as distant, peripheral, marginal. Here, the last vestiges of the idea of ‘remoteness’ falls down. Around 140,000 people live in Reykjavík. By comparison, Berkeley, California has 120,000 inhabitants. Should it, too, be considered remote?

Quiet high streets

There are, of course, huge differences between countries and how they classify and treat their peripheral communities, but as I experience more and more so-called remote locations, I find myself in many cases watching the same patterns unfold. Understanding now that remoteness is not only about geography, I watch it play out in the quiet, compounding effects of disconnection—not just from other places, but from within. When infrastructure fades, it is not just a matter of inconvenience, of longer drives or slower post delivery. The community itself begins to fray. The high street shrinks, and so do the casual encounters that once shaped daily life. Fewer shops mean fewer reasons to walk through town, fewer chances to stop and talk. Neighbours stop knowing one another. Schools close, and suddenly families must travel for education, spend more time away, and begin to feel that perhaps their future lies elsewhere. The connections that held people together—some formal, some invisible—start to loosen. How can people advocate for something they no longer feel rooted in?

Redefining remoteness

The idea that such places are destined for decline is not a neutral observation—it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. The erosion of local services is often framed as an inevitability, a slow erosion of autonomy disguised as the natural course of things. But in reality, it is a series of choices. Valuing these places for what they are—not for what they are missing—could shift the conversation entirely. Because in the end, remoteness is not about miles on a map. It is about whether a place is seen, supported, and allowed to imagine a future.

Perhaps this is why I resist the word "remote"—not because it fails to describe a certain kind of experience, but because it imposes a separateness that does not exist. It suggests isolation where there is connection, distance where there is community. It implies seclusion not just from services or infrastructure, but from relevance itself. Avoch was never remote to me. Instead, in my experience there, it was central, pivotal. Even now, living in another place so often labeled as remote, I see the same truth: what matters is not how far we are from some imagined core, but how we define the centre itself as the networks of care, culture, and resilience that bind us together. The real question is not how to make these places less remote, but how to dismantle the flawed perception that they were ever distant at all. If we placed communities at the heart of our thinking—rather than measuring them against an arbitrary elsewhere—then remoteness would cease to be a deficit, and simply become another way of being in the world.